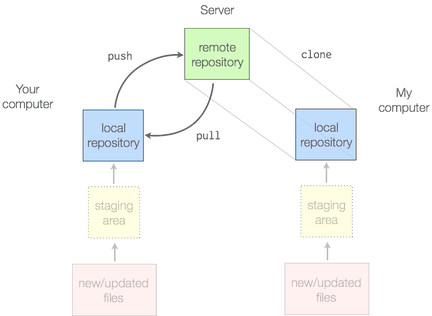

Normally when people talk about source control, they focus on collaboration: If you're collaborating on code and you're not using source control, you're doing it wrong! If you're collaborating with others, source control looks roughly like this:

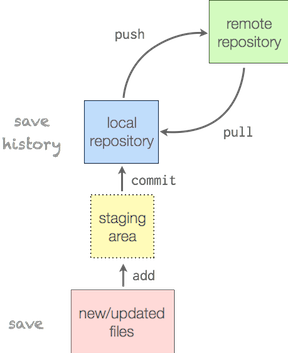

If you're just working on your own code, though, you should still be using source control. The soloist's workspace will look something like this:

Whether or not you have a remote repository depends on how much you trust your hard drive. If the above doesn't make sense, don't worry: These diagrams should (I hope) become clear shortly.

Here I'll be focusing on git, since it's what I use for my day-to-day routine, but any (distributed) version/source/revision control software will do. Some commands will differ for other software, but the basic concepts are still the same.

Motivation

This is a text version of a presentation I gave for my old lab group---back in the day when I was in academia. If anyone needs to adopt source control, it's scientific programmers: Scientists often develop code for themselves (collaboration often focuses on the results, not the code), so we're prone to think that source control is not relevant. The purpose of this article is to convince you that source control is important---even if you're the only one looking at the code.

Here's why you should be using source control:

- (Unless you have unit tests) There are often huge time gaps between breaking code, and realizing that your code was broken. Source control remembers when you don't.

- You should document your rationale for changing code. (commit message)

- It's key to reproducible research: You keep a lab notebook for a reason (your memory sucks). Version control is your code notebook.

Because this motivation part is so important, I put this into context with real-world examples below.

Basic Concept

- Save code as logical sets of changes and write a good description of why you changed it. (git commit, git add)

- Now you have a history of changes, that means you can:

- look back at your rationale (git log)

- change back if you need to (git checkout)

- find out where things went wrong (git blame, git bisect)

- remove code with the knowledge that you can easily go back

Why you should use source control

The purpose of this article is to convince you to use source control, so I want to give concrete examples of how source control helps you. These examples are taken from a Matlab code base that I adopted. In addition to my frustrations with dealing with Matlab (<3 Python), I had to navigate a code base that was sorely lacking the benefits of source control, which is what prompted my original presentation.

All examples are taken from real changes that I made to my adopted code base. Apologies to the original authors of this code.

You're already trying to fake it!

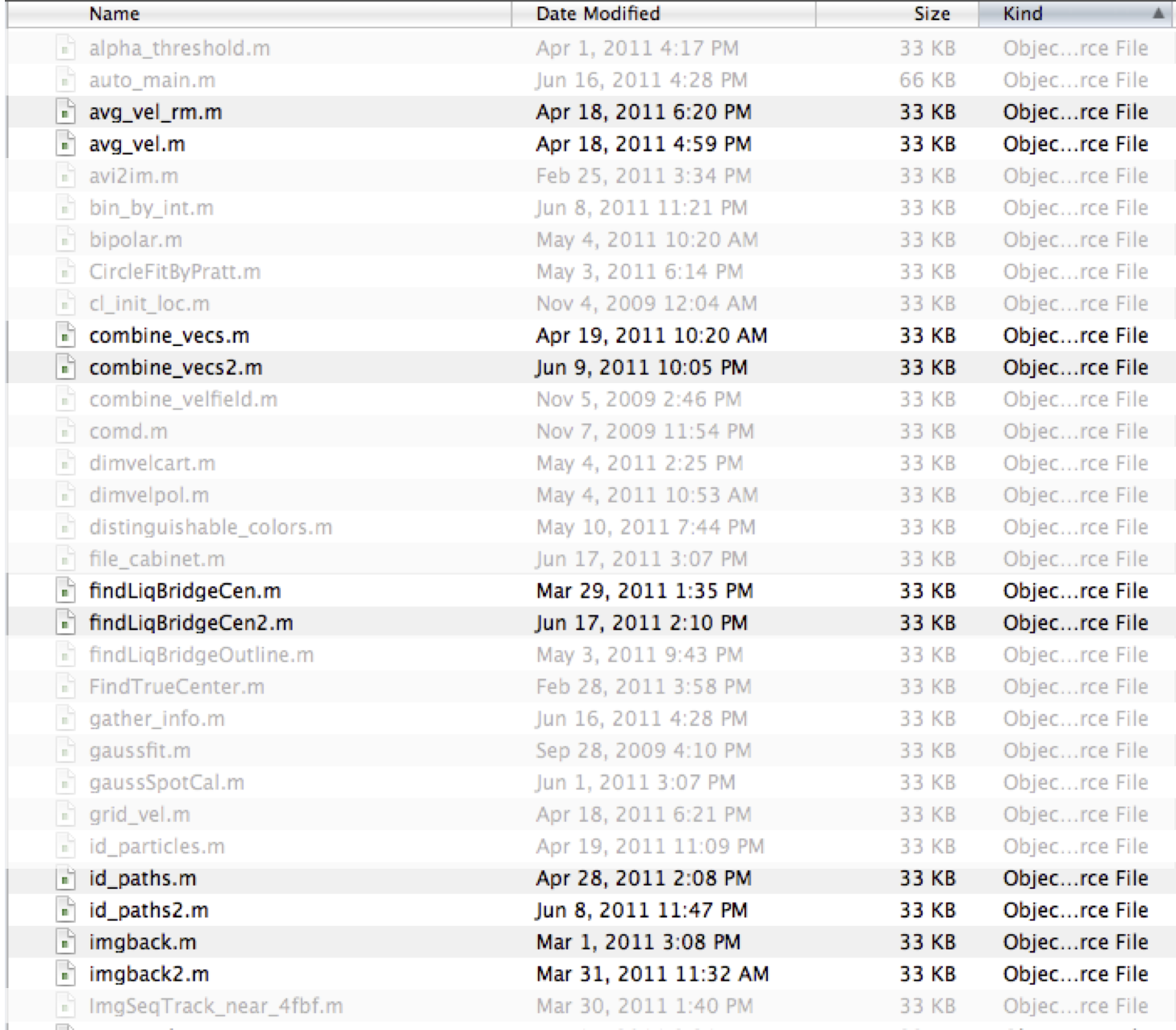

Here are some files from the code base I adopted.

You can see there are some newer versions of some files, but the author didn't want get rid of the older files ... just in case. Or wait, are some parts of the code still using the older versions? Sure, you can easily search (grep, grin, ack, whatever), but don't make me do extra work: I'm lazy.

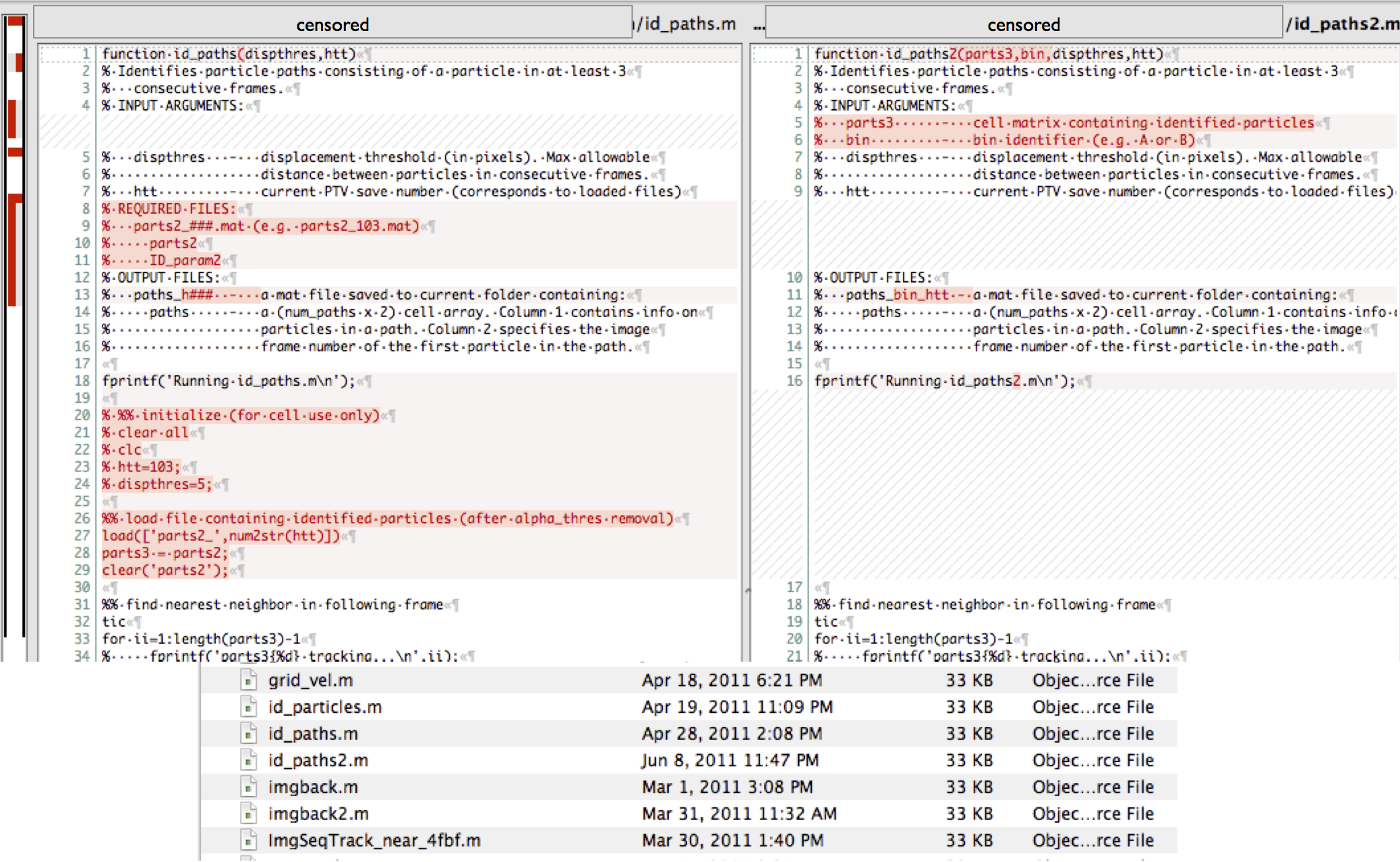

Let's look closer at the two duplicates at the bottom: id_paths.m and id_paths2.m. Here's is a diff of those two files:

Note that these files were a few hundred lines each, but the only difference between these two files are the lines highlighted in red. If there's a newer version of something, just keep the newest version! Version control will allow you to go back if really need to; otherwise, it's just a distraction.

You don't delete enough code!

(or: "Stop commenting out code and delete it already!")

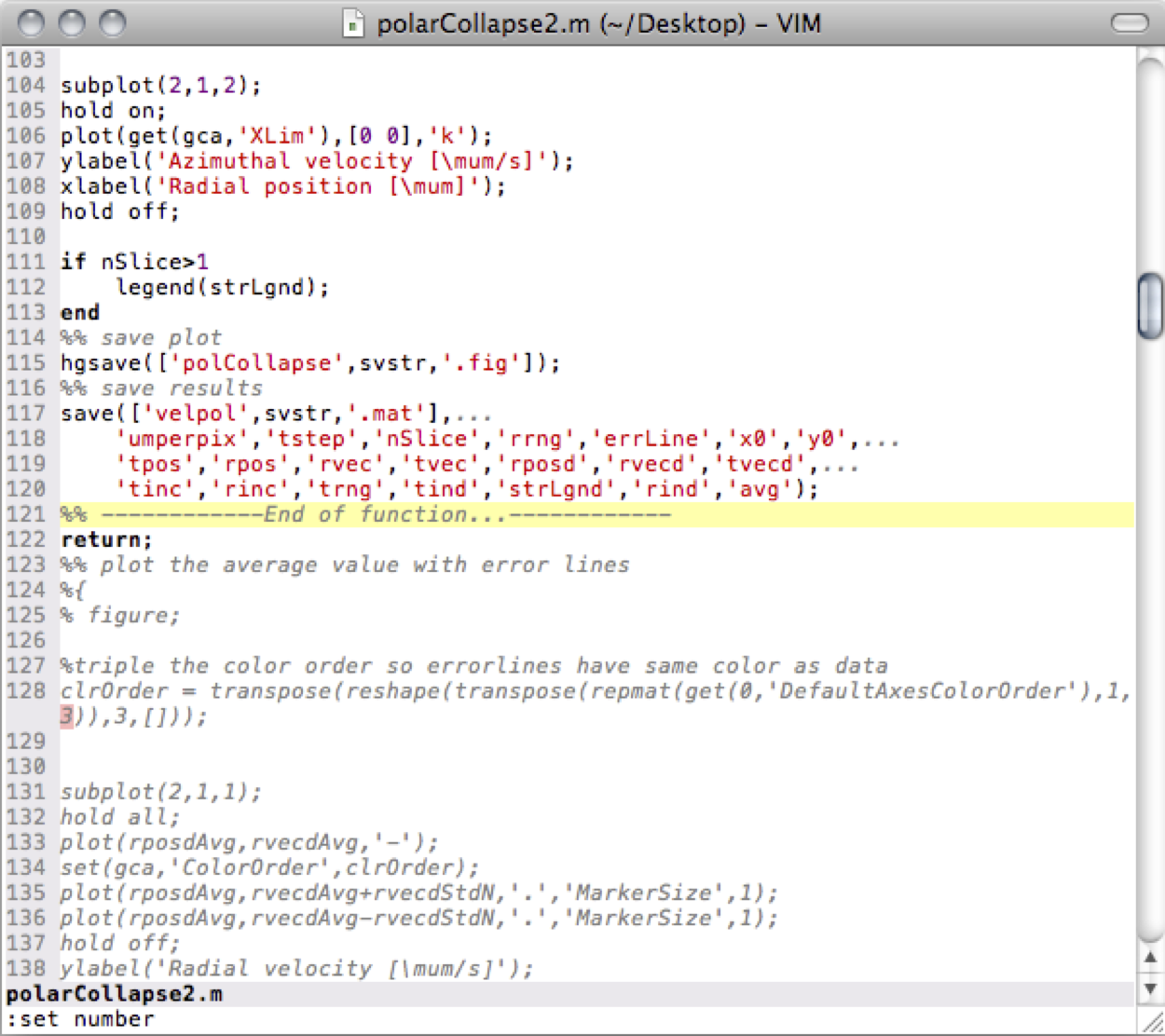

Sometimes you add debugging code when you're developing your algorithms, but the final product shouldn't have the code, so you do this:

Notice the return statement in the middle of that code block. What you don't see above is that there are a few hundred more lines of code that never get run because of the early return statement. Keeping all that code around makes it harder for you when you revisit the code. If you want to keep some debugging code, save that separately so that you can easily focus on the important stuff.

The basic commands

Git is notoriously complicated (and inconsistent). That said, if you stick to some basic commands, you can get pretty far along.

git init: Create a repository

This is important to know, but it isn't that exciting. You just go into the directory that contains all of your code (subdirectories will be included) and run git init to create the git repository (i.e. "repo"). This just needs to be done once per project.

Just think of the repository as a place where the history is being stored. A lot happens behind the scenes but who cares. (Maybe you care, but only after you really know how to use it.)

git add and git commit: Save changes

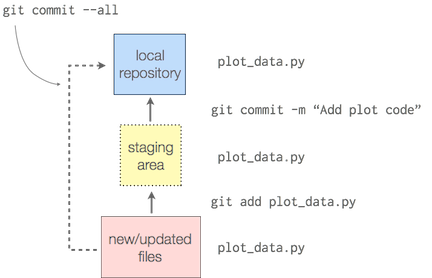

The concept of add and commit can be a bit confusing, especially if you're coming from some other version control systems. Many other version control systems just do what's equivalent to git commit --all (or git commit -a).

So let's assumed that we're just committing everything for now. This basically saves all your changes... "But wait, I've been saving my changes in my editor/IDE; hell, it even auto-saves."

The power of committing your changes to git is that you save the history. This concept is much more powerful than something like Time Machine. You had a reason for changing your code; you should document it (e.g., "Fix for when the signal is all zeros", "Update code to <this paper that improves on the original algorithm>"). Sure you could add a code comment to (poorly) document a few lines that changed, but what if those changes spanned multiple parts of the code. Your commit (and descriptive commit message) groups those logical changes together.

After you get into the habit of committing your changes using git commit --all, you'll want to evolve towards explicitly calling git add to specify which files you want to add to a specific commit. This helps you group your changes better and helps you write a better, more descriptive commit message.

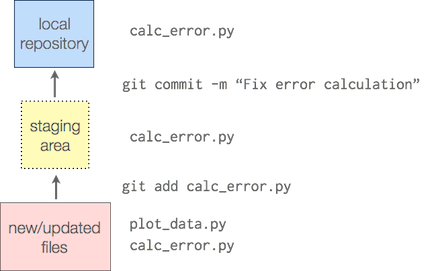

git add: Organize your save

We're not always great at concentrating on a single change. Explicitly specifying the files you want to add to the commit will force you to be more organized about the changes you made.

git add puts your changes into what's called the "staging area", and then then you call git commit to commit everything from the staging area.

More advanced: If you've made changes that aren't really part of the same fix/feature/whatever, you can add specific lines, but that's for another post.

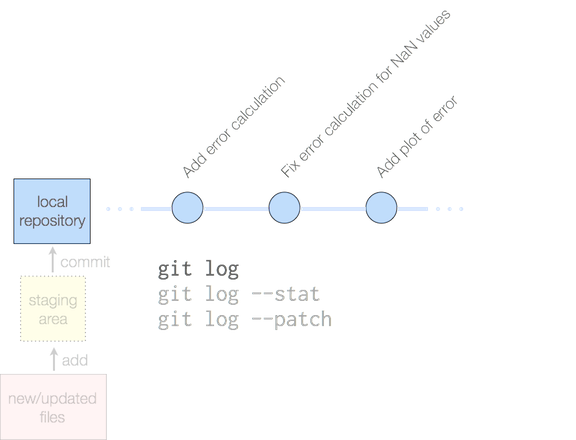

git log: Your code history

The log is your code notebook. You have a history of all the commits you have made. Most scientists want a history of the calculations they've done with all the missteps and epiphanies documented. Sometimes you just don't remember why you did something. This is a quick way to look back in time when your memory fails you.

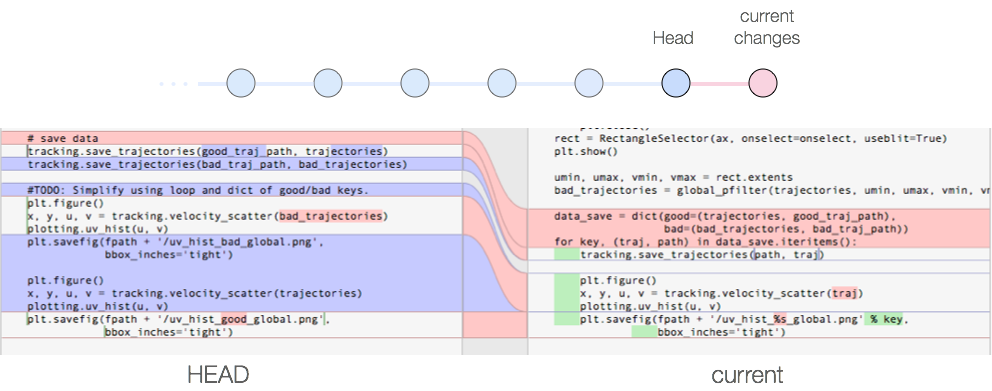

git diff: What did I do?

(or: "Finally! this works. Wait. What actually fixed the problem?")

You've made a ton of changes to fix some bug or add some feature. Inevitably, you've made some changes that weren't really part of the feature (e.g. print statements for debugging). git diff allows you to check what has changed from the original implementation.

More advanced: If you're using the staging area properly, you call git diff --staged to make sure that all the code you've added really pertains to the (very descriptive) commit message you're going to write.

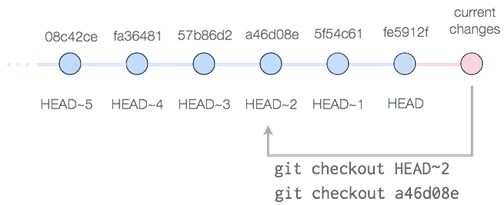

git checkout: Revisit old code

(or: "Argh, I wish I hadn’t made these changes!")

"I know my function didn't behave this way before,... wait am I sure about that?" Well, you can always go back to old code by checking out an older version.

Now you can try it out to see if this random dataset actually worked with the old code and figure out what changed.

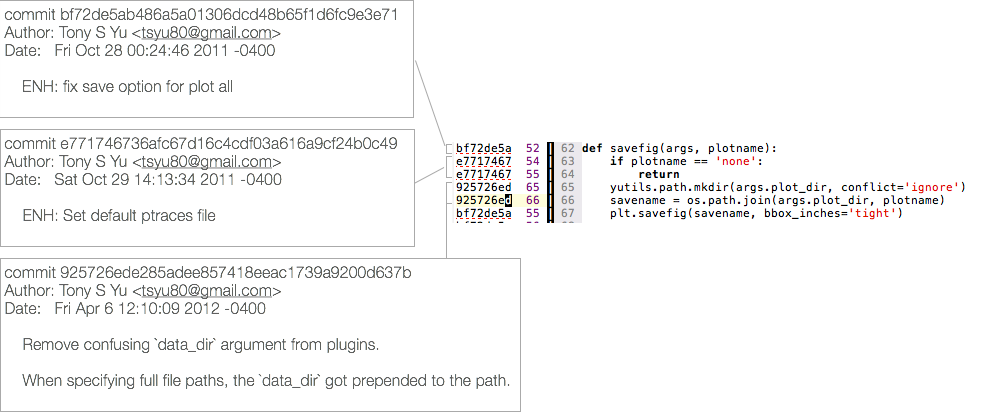

git blame: When and why was this line added?

We've all looked at some part of our code and forgotten why we added needed it. git blame allows you to look each line of a file and figure out when it was added, and your commit message tells you why you added it.

Note that this only works well if your commit messages are informative. Otherwise, you still don't know why you wrote that perplexing line of code.

Summary

Stop trying to invent your own version control (i.e. don't write file that look like: my_script.py/my_script_2.py, solver.py/solver_old.py)

Reproducibility and history are very important (especially for scientists)

The basic usage of git is pretty simple. (If you're not comfortable on the command-line though, there are tools to help you out---see below.)

- Good commit messages are important

- Bad: "update code"

- Good: "Add calculate_standard_error function", "Fix for NaN inputs"

This describes git usage from the perspective of someone who's comfortable using the command line. Since programming isn't the focus of many scientists, you may not be as comfortable on the command line. Fear not: There are many GUI clients for git. I can't really throw my weight behind any of them since I don't use any of them, but SourceTree and SmartGit both look pretty popular.

In the end, I don't think I was successful in converting any of my fellow scientists to use source control. The problem is that it takes a bit of discipline at the very beginning, and, like many things in life, it's hard to see the benefits until you've already invested a bit of time to learn it.

Now that my day job is software development, I don't need to convince anyone of the benefits of source control. But maybe there's a scientist out there who does need some convincing ...

Comments

comments powered by Disqus